Some lives are marked by struggle from the very beginning. The story of Serkan Bayram, a Turkish lawyer, lawmaker and disability rights activist, is one of resilience born from the ashes – quite literally. In 1974, during the turbulent days of the Cyprus Peace Operation, Bayram was born in Erzincan. A year later, a tragic accident left much of his body burned in a fire while his mother was working in the fields. Carried on a mule to the nearest town of Refahiye, he was treated in intensive care for 40 days. On the 41st day, he opened his eyes, marking not just a return to life, but the beginning of a lifelong determination to rise beyond adversity.

Bayram’s youth was anything but easy. He faced social prejudice and emotional isolation. He would hide his hands and choose window seats in buses and quiet corners in mosques – places where he felt less visible. But within, a stubborn voice always whispered: “Don’t give up.”

That voice carried him to Istanbul University’s Faculty of Law, where he graduated with honors. Yet even academic success couldn’t shield him from systemic discrimination. Though he passed the written portion of the judicial exam, he was rejected in the interview stage on the grounds of “lack of physical integrity.” Article 8 of the Law on the Council of Judges and Prosecutors at the time excluded anyone whose appearance could be perceived as “unusual or discomforting” to the public.

But Serkan Bayram is not one to be easily deterred. Instead of retreating, he pushed forward – earning a master’s degree at Marmara University and eventually turning to politics. At age 41 – the same symbolic number as the day he survived the fire – he was elected to Parliament, representing his home province of Erzincan.

One of his first actions in Parliament was to abolish the very regulation that had once barred him from becoming a judge. With unanimous support from all parties, Bayram successfully removed a clause that was both unconstitutional and inhumane. Today, Türkiye has disabled judges and prosecutors – proof that governance depends not on physical form but on moral vision and mental acuity.

From personal to collective

Bayram’s story is not merely personal; it’s national. He has worked to ensure that others don’t endure the same institutionalized barriers he faced. Under his watch, thousands of people with disabilities have been appointed to public service through the EKPSS system. He has championed home care support, special education initiatives and rehabilitation centers, transforming disabled citizens from passive recipients of aid into active contributors to society.

But his ambition reaches far beyond Türkiye.

“There’s UNICEF for children and U.N. Women for women,” he says. “But there is no global body for people with disabilities, though they number over 1.5 billion worldwide. That needs to change.”

Bayram has formally proposed the establishment of a United Nations Center for Disability Rights, with its headquarters in Istanbul. He presented this visionary idea at the U.N.’s 56th session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva, in a panel co-sponsored by Türkiye, China, Greece and Bangladesh. The initiative aims to promote accessibility and development for not only people with disabilities, but also the elderly and other vulnerable populations. His proposal received enthusiastic support from several international delegations – another milestone in his mission to build a world where physical differences do not limit opportunity.

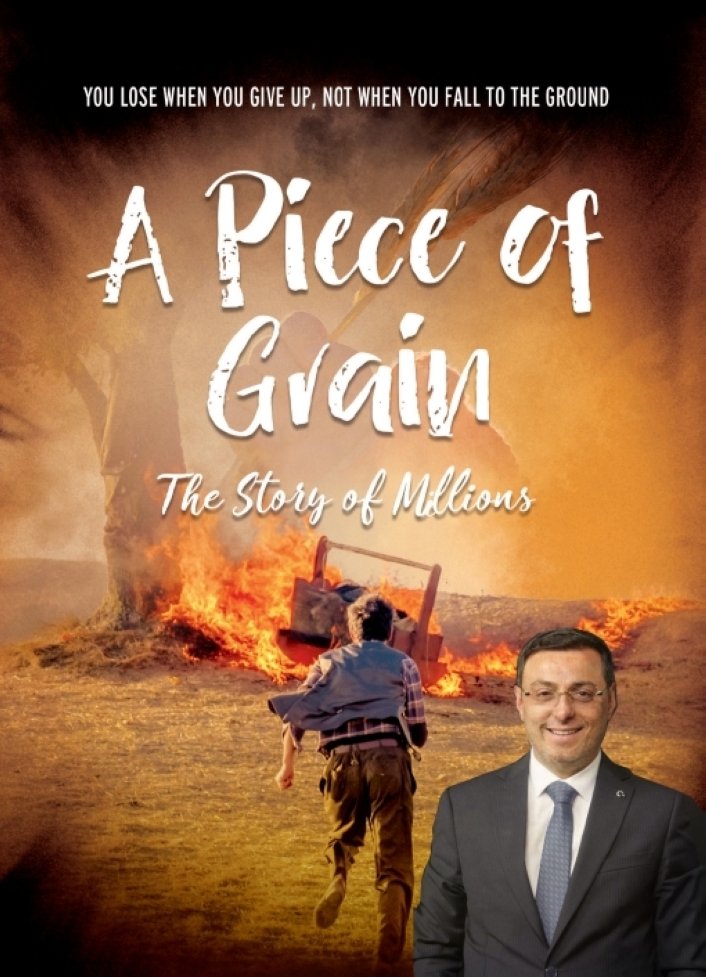

‘A Piece of Grain’

At the heart of Bayram’s global outreach lies a remarkable film: “A Piece of Grain” (“Buğday Tanesi”), which chronicles his life story. The film, supported by the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), has reached over 40 million viewers worldwide – screened on Netflix, Turkish Airlines flights and at prestigious international film festivals from Cannes and New York.

Why a piece of grain? “Each of us is a seed,” Bayram says. “Small and fragile, but when nurtured, we multiply, grow and nourish.”

The film is not just a biopic: It’s a mirror held up to society. It teaches empathy, urges reflection and most importantly, motivates. After a screening in the Netherlands, a man approached Bayram with tears in his eyes: “I have money, health, a family … and yet I’m unhappy. But after watching your film, I realized: If you can achieve all this, what excuse do I have?”

That’s the power of “A Piece of Grain.” It’s not just for people with disabilities; it’s for everyone seeking hope, purpose and the courage to keep going.

The international community has also taken note of this. “A Piece of Grain” was honored with the Human Dignity Award in Berlin, received the Best International Film Award at the New York International Film Festival and was screened at the European Parliament as an example of cinematic activism. Most recently, in Japan, it was awarded the Best Inspirational Feature at the Tokyo International Film Festival – a testament to the film’s universal emotional resonance.

Each award, Bayram says, belongs not just to him, but to everyone who has ever been told “you can’t.” It is a celebration of resilience, breaking barriers and transforming personal history into global awareness.

Teachers who plant seeds

Bayram never forgets those who believed in him. He recalls his teacher, Ali Gürek, who once gave him a lead role in a school play and ensured he sat comfortably in class due to his left-handed preference. Years later, Gürek saw Bayram mention him on television and sent a message through another MP: “I’m proud of you. I still have so much to tell you.”

These moments of support in early life, Bayram says, are what truly empower individuals. “It’s not about telling someone what they can’t do – it’s about asking them what they can do.”

This philosophy now shapes his TV appearances, public speeches and mentorships. He regularly showcases the stories of disabled entrepreneurs, artists and engineers, giving them the spotlight they deserve. His underlying message? “We’re all potential candidates for disability. Life is unpredictable, but dignity should never be conditional.”

Global voice with local roots

Bayram’s international recognition continues to grow. He has spoken before the U.K. Parliament, the European Parliament and the Council of Europe. He has received multiple honorary doctorates and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by various religious and academic institutions. His recent audience with Pope Francis in the Vatican further underscored the universality of his mission: human dignity knows no borders.

“Let’s create a global model from Türkiye,” Bayram insists. “Let Istanbul be the home of the first U.N. Disability Rights Center. Let us set the standard.”

Final words from the survivor

What makes Serkan Bayram’s story so compelling is not just his survival – but his refusal to surrender. He has transformed pain into purpose, tragedy into triumph and exclusion into advocacy. His journey is a call to action for all of us, to reflect, to empathize and above all, to act.

“Being disabled is not a weakness,” he says. “It’s a different kind of strength. The real disability is the absence of love.”

And, in his own timeless words: “You don’t lose when you fall, you lose when you give up.”

Be First to Comment